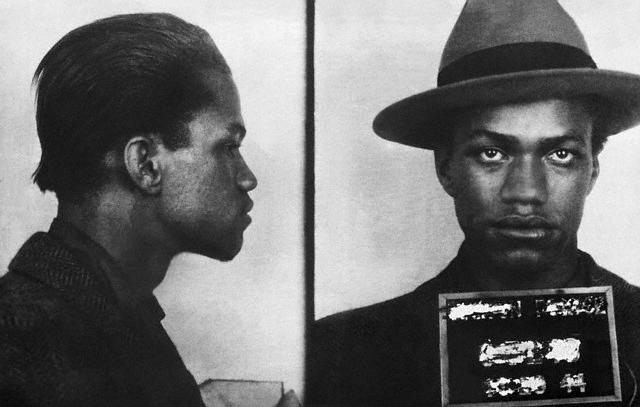

The mugshot of a young Malcolm X, arrested for his numerous 'hustling' activities, before he became an outright revolutionary

In my previous posts I explored selections from the historiography of the Subaltern Studies Group that impacted A Nation Under Our Feet. When discussing the formative influences on his conception of subaltern resistance, Steven Hahn cites only two books on explicitly American topics: Eugene Genovese’s landmark Roll, Jordan, Roll (1974), and Robin D.G. Kelley’s Race Rebels: Culture, Politics, and the Black Working Class (1994). While the influence of Genovese appears to be ubiquitous in nineteenth century American historiography, this week I decided to read Race Rebels in order to see what Hahn took away from this lesser-known work.

Kelley’s book is a rich collection of essays on “writing black working-class history from way, way below” (1). Thoroughly and openly working in footsteps of C.L.R. James, W.E.B. DuBois, and James C. Scott’s concept of “infrapolitics,” much of Kelley’s book revolves around a central question: “If we are going to write a history of black working-class resistance, where do we place the vast majority of people who did not belong to either ‘working-class’ organizations or black political movements?” (4). Kelley thus seeks to account for the wide range of life experiences between outright domination and open rebellion, and in doing so he succeeds in painting a three dimensional portrait of the African-American experience of the last century or so. The book includes essays on topics from African-American volunteers in the Spanish Civil War, the resistance of McDonald’s employees, early 90s gangsta rap, Malcolm X (pictured above) and the politics of the zoot suit, and struggles over the right to public space.

For the uninitiated, infrapolitics is the term coined by Scott to describe both the deliberate invisibility of “everyday resistance” and the “infrastructural” role these subversive activities play in supporting future revolutionary outbursts. The first part of Hahn’s A Nation Under Our Feet, which describes black political activity under slavery, is a useful example of the infrapolitical framework, and it is clear that Kelley played a key role in shaping his analysis. Chapter two of Race Rebels, “‘We Are Not What We Seem’: the Politics and Pleasures of Community,” is particularly important in this regard as it explicitly puts forward the notion that the oft-neglected study of the home may hold an important key in coming to understand everyday resistance: “Once we begin to look at the family as a central (if not the central) institution where political ideologies are formed and reproduced, we may discover that households themselves hold the key to explaining particular episodes of black working-class resistance” (37). While much, perhaps most, scholarship on resistance focuses on the point of production, Kelley notes how feminist historians have emphasized the ways in which types of class consciousness are often learned at home, before an individual ever enters the workplace. Perhaps, then, the study of the family and kinship networks may be the missing link in explaining the resilience and continual reproduction of black working-class resistance. Kelley notes, for instance, that family membership in mutual aid associations and religious organizations helped to build and maintain a collectivist, working-class culture (38). In this vein, Kelley describes the role of community-financed black churches in encouraging the growth of labor unions in the South (41-43).

But the realms of the sacred were not the only grassroots arenas of community-building; the more profane centers of commercialized leisure were also instrumental in inculcating an autonomous black consciousness. These “bars, dance halls, blues clubs, barber shops, beauty salons, and street corners” (44) were key in forming a “secular congregation” (45) under the Jim Crow structures of racial and class oppression. However – our class will be happy to know – Kelley does not automatically or necessarily conflate autonomy with resistance: “I am not suggesting that parties, dances, and other leisure pursuits were merely guises for political events, or that these cultural practices were clear acts of resistance. Instead, much if not most of African American popular culture can be characterized as, to use Raymond Williams’s terminology, ‘alternative’ rather than oppositional” (47). For instance, these spaces and practices could also reinforce rank consumerism and misogyny, trends that are able to coexist with the more oppositional characteristics of autonomous black cultural spheres (later in the book, Kelley also extends this insight to his discussion on the politics of early 90s gangsta rap).

Kelley further distinguishes himself from the pack of the “it’s all resistance” school in his discussion of the issue of black collaborators with white supremacy. Historians have to pay careful attention to how struggles are continuously made and remade, and note the multitude of possible (and actual) reactions to conditions of oppression in any given situation:

“That stool pigeons [informers or collaborators] can exist in black communities, and that their reasons for turning informant might be motivated by the same circumstances that led many of Hosea Hudson’s comrades into the Communist Party (i.e., joblessness and poverty), reinforce the idea that neither mutual oppression nor common skin color alone explain black working-class solidarity….When we search for the locus of working-class opposition, we ought to look not only at antiracist activities or workplace conflicts but at the dynamic processes by which social and cultural institutions were constructed and time and space for leisure appropriated” (52).

It is easy to see the impact that Kelley’s nuanced analysis of black infrapolitics had on informing the analytical framework A Nation Under Our Feet. Hahn’s conception of the political, particularly his emphasis on kinship networks as well as spaces of communication and autonomy, were clearly shaped in the wake of Kelley’s inventive scholarship.